Abstract

You already know what learning outcomes are. You’ve made more than enough LibGuides. Now you’re ready to do something different. Bring a learning outcome that you’d like to develop into a learning object, and spend the preconference workshop applying learner-centered and design-thinking frameworks to turn ideas into actionable prototypes ready for user feedback. This workshop will help you think creatively about pathways to a publishable prototype, paying special attention to varying resources and expertise. The guiding principles behind this workshop are to build imperfect solutions quickly and on purpose, to target highly specific outcomes, and to start with small and manageable projects. This iterative process begins with identifying learner challenges, then moves to imagining and creating focused interventions and partnering with learners for feedback and improvement. We aim to break down perceived barriers and build confidence and competence in designing a learning object, regardless of technical expertise or educational background.

Brecher Cook, D., & Worsham, D. (2018, April). Let’s Build Something!: A Rapid-Prototyping Instructional Design Workshop. Pre-conference workshop presented at the 2018 CARL Conference, The Academic Library in Times of Change, Redwood City, CA.

The following overview of the workshop comes from the conference proceedings:

A Learner-Centered Design Thinking Approach to Instructional Design

In this pre-conference workshop, we proposed that design is best learned by designing, that theory is often best understood through practice, and that the creative process requires safe spaces and open stretches of time to explore, experiment, and iterate. Rather than learning about instructional design, in this workshop we strove to create an environment in which participants did instructional design through iterative rapid-prototyping, divergent thinking, constructive feedback, and a fearless exploration and expansion of the adjacent possible. We utilized two conceptual frameworks to shape the day: “design thinking” and “learner-centeredness.”

Design thinking is increasingly recognized as a key skill in changing academic library environments, with utility across multiple areas of our services, from instruction and research assistance, to collections and spaces. Design-oriented approaches, particularly those focused on rapid, iterative development, are well matched to the current higher education environment, in which diverse instructional contexts and varying and evolving learner needs require our services to be more flexible and responsive. Specifically, in this workshop, we were interested in utilizing and adapting the design thinking framework from the Stanford d.school, which focuses on a human-centered practice and encourages creators to deeply empathize with end users to build a relevant and useful tool. This type of design thinking involves an intentional and ongoing engagement with users, from defining the challenge to be addressed to testing various iterations of tools and strategies in a collaborative mode with representatives from the ultimate audience.

We felt that this design-thinking approach aligned strongly with the concept of “learner-centeredness” from the education literature, as both ideas focus on empathizing with, understanding, and responding to the needs of users (and learners) at the heart of the process. Learner-centered strategies for instructional design include engaging learners early in the design process to learn more about their strengths and needs, incorporating best practices drawn from the science of learning, and pursuing universal design and accessibility at every stage of the process.

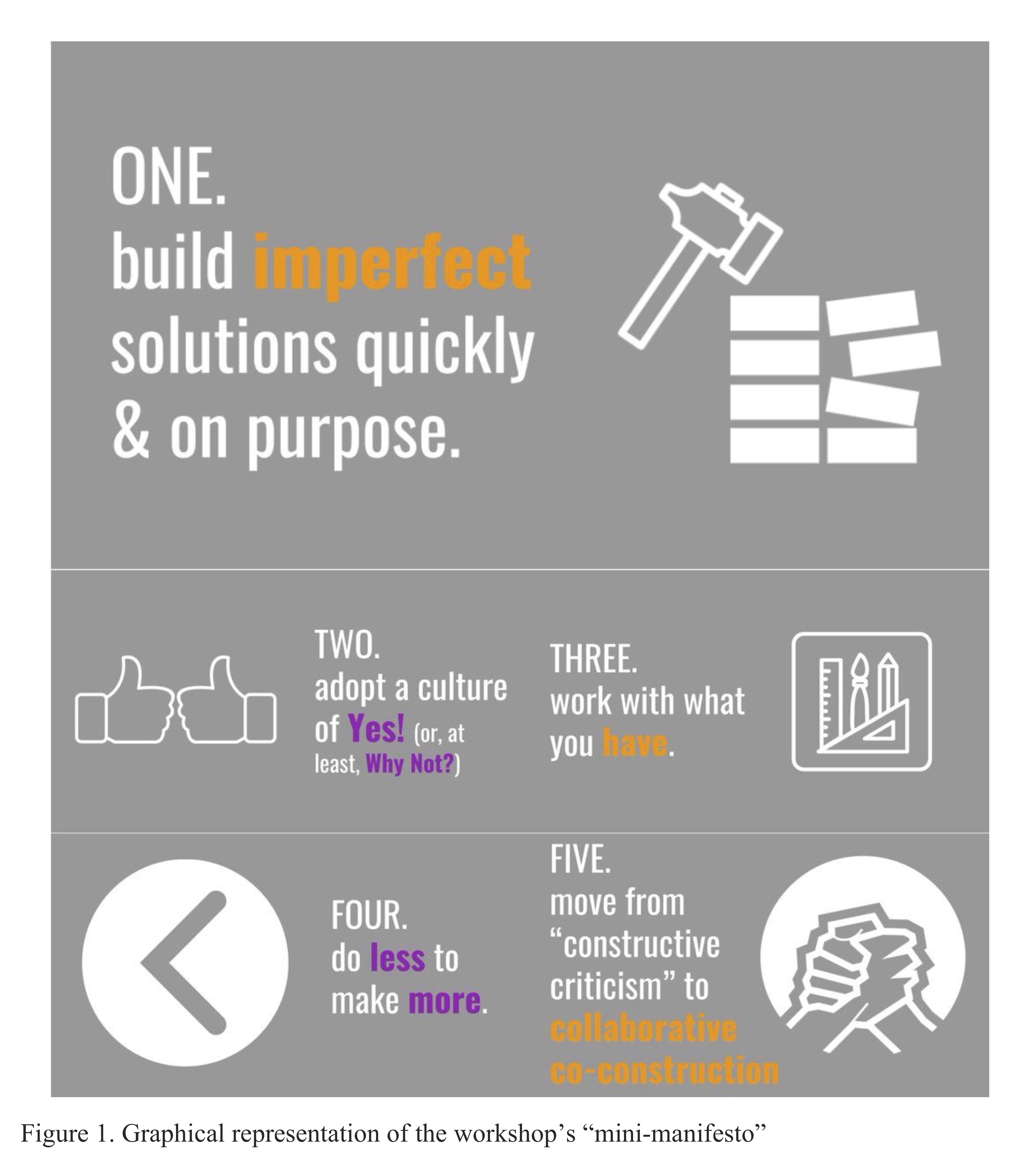

With these two framing concepts in mind, the goal of the workshop was to take participants from imagining an information literacy-focused instructional challenge to walking away from the session with a workable prototype that they could then polish and refine at their home campus. To facilitate this process, we proposed five overarching strategies for the day (and to be taken forward in future instructional design work):

- Build imperfect solutions quickly and on-purpose.

- Adopt a culture of “Yes!” (or, at least, “why not?”).

- Work with what you have.

- Do less to make more.

- Move from “constructive criticism” to “collaborative co-construction.”

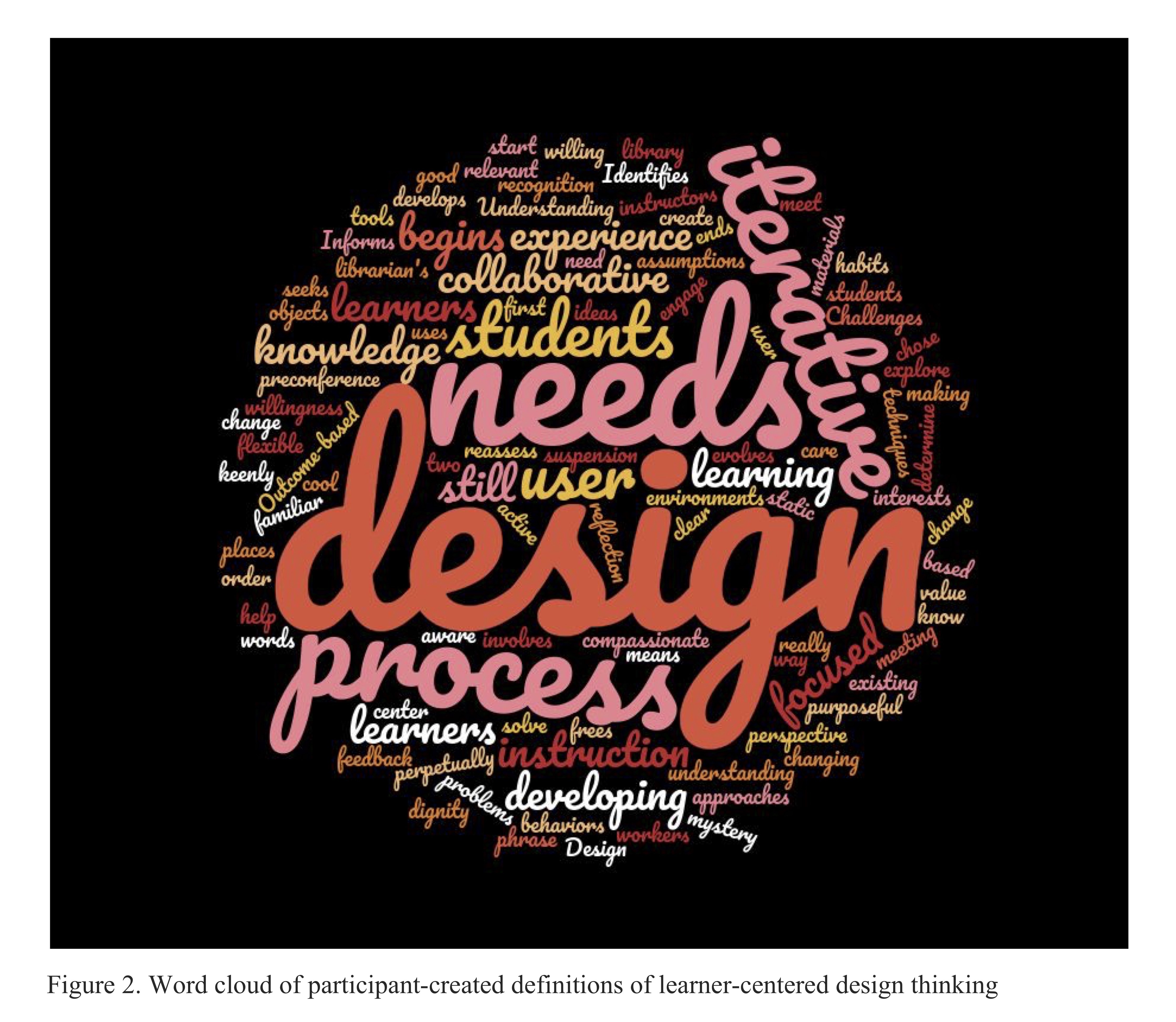

Next, workshop participants reflected on and shared their ideas on learner-centeredness and design thinking, collaborating in a variety of ways to describe and define these concepts.

Approaches for Defining Context, Learning Challenges, and Breakthroughs

Grounded in this collaboratively constructed definition and the five overarching strategies for the day, participants then completed a series of design thinking activities focused on various learning contexts and challenges. In these activities, all of which have related handouts and examples (see Appendix 2 - The Build Something Toolkit), participants alternated between 4-6 minutes of independent brainstorming, followed by collaborative feedback and idea generation with a fellow workshop participant working on a similar instructional challenge. Our goal was to provide participants with a reusable set of tools and techniques for learner-centered design that could be applied in a variety of contexts at their home institutions and also provide ample opportunities to get feedback, advice, and insight from their colleagues.

Empathy Mapping

The first of these techniques, empathy mapping, situates design ideas in real-world learning contexts and centers design thinking around learners and their goals. As an initial step in a learner-centered design process, an empathy map helps designers rapidly develop insight into key challenges and breakthroughs in the learning process.

Learning Journey Mapping

After using their empathy maps to explore a learning challenge and identify breakthroughs, participants selected a specific challenge to further explore using a journey map. Journey mapping helps designers break down complex learning outcomes into smaller tasks, emphasizing the learning process and uncovering potentially hidden steps and challenges. One of the primary benefits of learning journey mapping is that it helps narrow and refine learning outcomes, leading to more realistic, manageable, and focused projects.

Rapid Prototyping & Feedback Strategies

As a part of our larger goal for the workshop to build confidence and break down perceived barriers to applying design thinking in library instructional contexts, we shared a highly iterative approach to rapid prototyping, demonstrating that it is possible to create 5 or more increasingly realized prototypes in just 90 minutes! These rapid prototyping activities allowed participants to take an idea they had developed through empathy and journey mapping and work toward a functional prototype.

Four Paths Prototyping

One of the most important concepts in design thinking is intentionally leveraging both divergent thinking (coming up with a variety of different ideas and possibilities) and convergent thinking (focusing and narrowing possibilities to select an initial approach). In the four paths prototyping activity, participants rapidly explored four different ways to approach an instructional challenge. This divergent process helps designers work past their initial assumptions and explore a wider variety of pathways and possibilities. In order to help participants overcome initial fears about the drawing aspect of four-paths prototyping, the presenters shared some of our own prototypes, demonstrating that advanced (or even basic) artistic skills are not required for this activity.

A key aspect of the four paths activity is that it is very fast. Participants were given five minutes to complete the activity. At first, completing the task in this time frame seems impossible, but as in the previous design thinking activities, the time limit helps foster rapid idea generation, reduce self-critique, and encourage fearless exploration.

Storyboarding & Wireframing

Participants were then asked to select one of their four paths ideas to flesh out during the rest of the workshop. Depending on the modality of the learning object, we provided storyboarding and wireframing templates for videos, online tutorials, and workshops, or participants could opt to just use blank paper to start sketching out a section of their prototype. Once again, we limited the amount of time for each iteration of the planning, giving participants 20 minutes for the first sketch and 15 minutes for a second draft, with time for collaborative and structured feedback in between. Finally, participants were given seven minutes to draft a plan for completing their project when they returned to their home campus.

Feedback Gathering Techniques

In between each round of storyboarding/wireframing, we provided a different, structured method for gathering collaborative feedback. These techniques included framing comments as “I like,” “I wish,” and “What if…?” and a more targeted user feedback interview protocol. Examples of these techniques can be found in Appendix 2. The Build Something Toolkit.

Finally, to facilitate transforming the prototypes into workable objects ready for use, we shared a crowd-sourced document (bit.ly/build-something-diy), filled with ideas for platforms and tools for creating polished projects, aimed at a variety of skill levels and price points.

Takeaways

Participants in the workshop each walked away with:

- A conceptual understanding of design thinking and learner-centeredness

- A reusable toolkit for engaging in a collaborative instructional design process utilizing these two conceptual frameworks

- An actionable prototype of a learning object or activity that they could then continue iterating, test, and complete at home

- A crowd-sourced list of tools of various costs and complexities for creating learning objects

References

- Action Verbs for Learning Objectives. Education Oasis. Retrieved from http://agsci.psu.edu/elearning/pdf/objective_verbs.pdf

- Both, T., & Baggereor, D. (2009). Design Thinking Bootleg. Retrieved April 10, 2018, from https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources/the-bootcamp-bootleg

- Gray, D., Brown, S., & Macanufo, J. (2010). Gamestorming: a playbook for innovators, rulebreakers, and changemakers. Farnham: O’Reilly. Retrieved from http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=562862

- Klipfel, K. M., & Cook, D. B. (2017). Learner-centered pedagogy: Principles and practice. Chicago: ALA Editions.

- Krug, S., & Matcho, M. (2010). Rocket surgery made easy: the do-it-yourself guide to finding and fixing usability problems. Berkeley, CA: New Riders.

- UCLA WI+RE (Writing Instruction + Research Education). Strategies for Research and Writing. Retrieved April 10, 2018, from https://uclalibrary.github.io/research-tips/

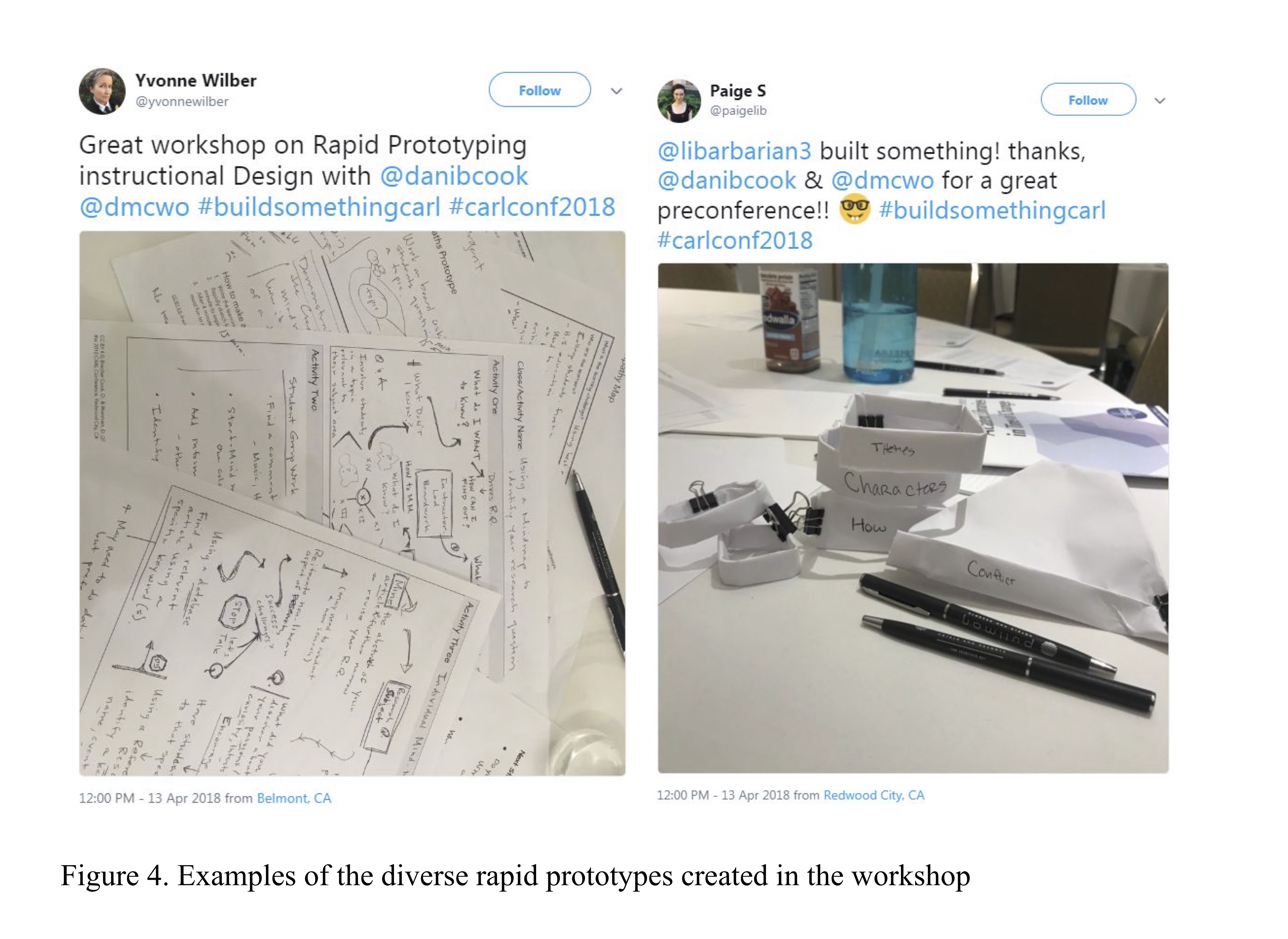

Conference tweets

@libarbarian3 built something! thanks, @danibcook & @dmcwo for a great preconference!! 🤓 #buildsomethingcarl #carlconf2018 pic.twitter.com/k4dWXUUk6B

— Paige S (@paigelib) April 13, 2018

#buildsomethingcarl with @danibcook and @dmcwo has been a fun instructional design workshop. I’ve already started building my prototype learning object in a Google Site. #carlconf2018

— Daniel Ransom (@ThePinakes) April 13, 2018

Great workshop on Rapid Prototyping instructional Design with @danibcook @dmcwo #buildsomethingcarl #carlconf2018 pic.twitter.com/LdwTGETUTe

— Yvonne Wilber (@yvonnewilber) April 13, 2018

Fantastic workshop on learner-centered design thinking! #carlconf2018

— Yvonne Wilber (@yvonnewilber) April 13, 2018